Why was the Viaduct Built?

Image: Historic England

The viaduct was constructed to carry the Great Northern Railway Company’s Derbyshire and Staffordshire extension “the Friargate Line” across the Erewash Valley. A combination of factors led to the creation of the new railway line, which included:

Breaking the Midland Monopoly (Coal)

In the mid 1800s, the rail network was owned by private railway companies. The Midland Railway was the dominant company in the region. The influential private coal owners in the Erewash Valley were keen to break the Midland Railway monopoly as the company controlled transport costs which elevated the price of coal. Those increased costs made the Erewash Valley Coalfield less competitive in reaching lucrative southern markets.

Creating new rail access to develop the coalfield

To the east of the Erewash Valley, The 10th Duke of St Albans had millions of tons of coal reserves on his Bestwood Estate but lacked access to the rail network to develop those reserves. The Duke was a powerful politician and a privy councillor in Gladstone’s government and an influential figure in securing Parliamentary approval (1872) for the new line.

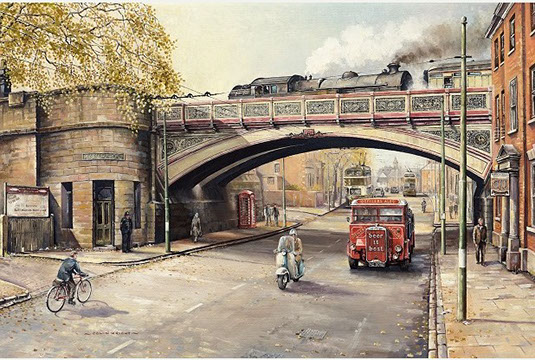

by Frederick Sargent

Breaking the Midland Monopoly – City of Derby

The Midland Railway was based in Derby but businesses and councillors in the city considered that the Midland monopoly was holding back the development of Derby. The Midland controlled the prices of goods coming in and out of the city. Businesses and councils lobbied Parliament for the city to be served by an additional railway company. The City of Derby were so desperate to break the monopoly of the Midland Railway that they let the Great Northern Railway build its line right through the heart of the city at Friargate.

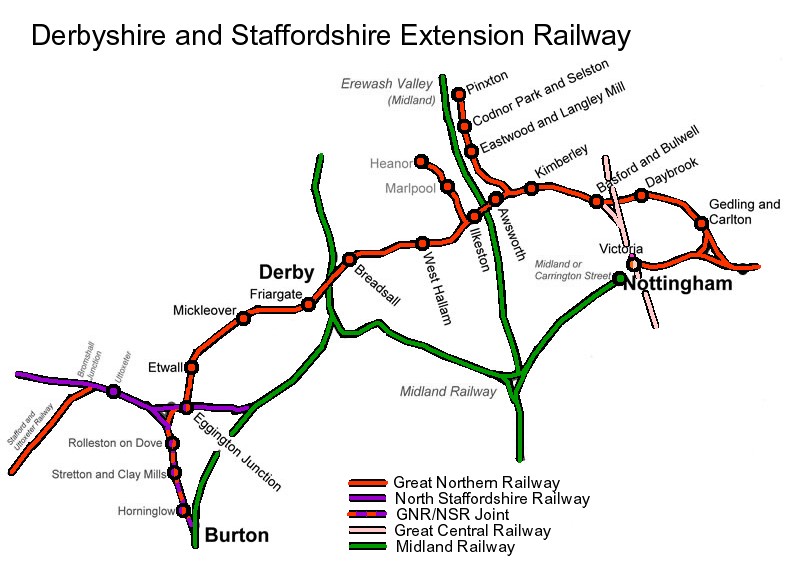

Act of Parliament 1872

An Act of Parliament was passed in 1872 giving The Great Northern Railway Company permission to build the Derbyshire and Staffordshire extension which is also known as the Friargate Line. The line went from Nottingham to Derby then on Eggington Junction in Staffordshire with branch lines running north into the Erewash Coalfield.

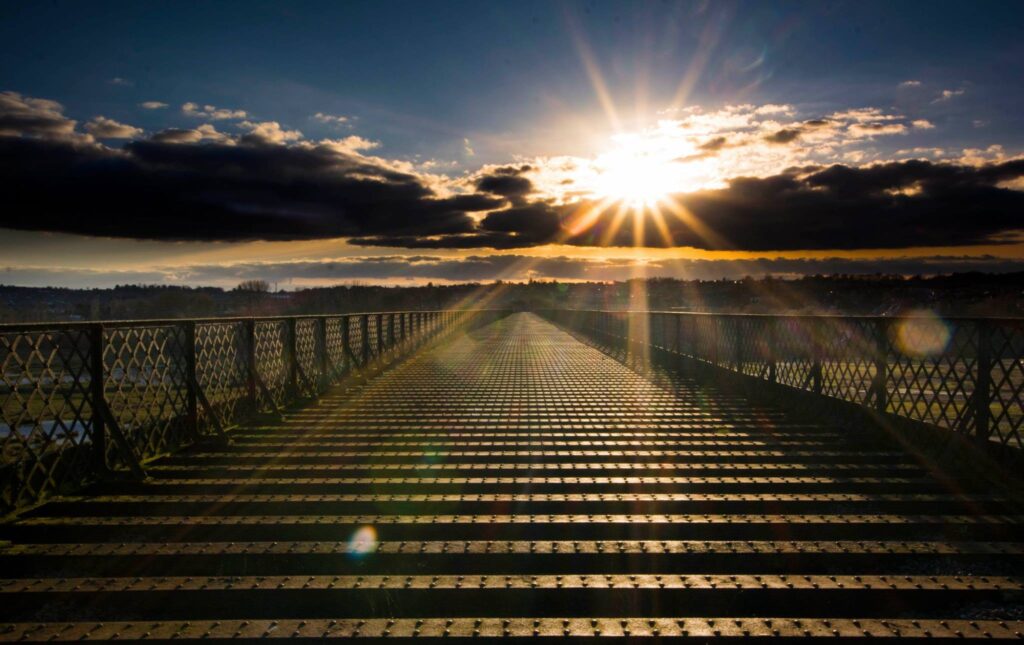

Image: John Speller

The Engineering Challenge

The construction of the line provided a significant engineering challenge as the easy geographical routes had already been taken. The biggest obstacle was crossing of the Erewash Valley between Awsworth and Ilkeston, an area honeycombed with mine workings. The iconic Bennerley Viaduct was constructed in an 18 month period in 1877 and 1878 as a bespoke engineering solution to overcome this engineering challenge.

Who Built the Viaduct?

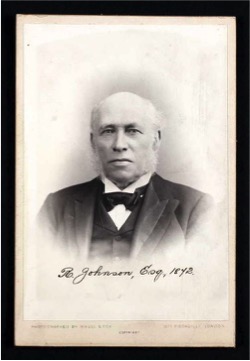

Engineers

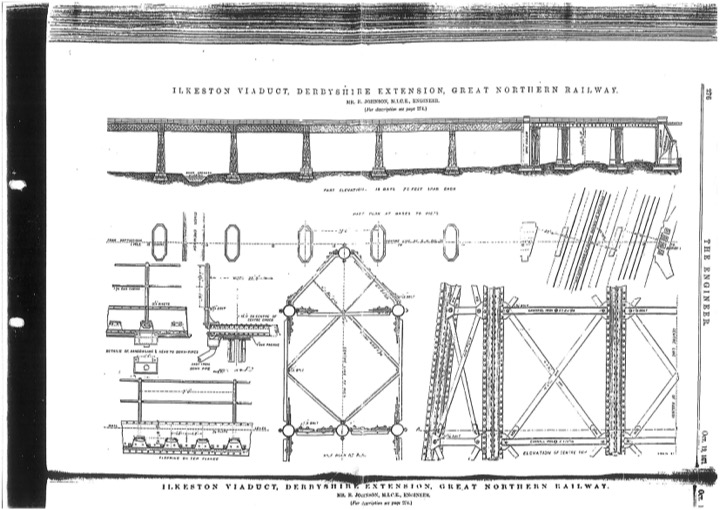

When the Act of Parliament was passed in 1872, the Great Northern Railway Company (GNR) instructed Richard Johnson, the Chief Civil Engineer and Samuel Abbott, the resident engineer to design the line and its structures including the viaduct. These brilliant and pioneering engineers boldly tackled the challenges of constructing the line with an ingenuity that embodied the spirit of the era.

Constructors

The viaduct was built and assembled by Benton and Woodiwiss, a famous Derby based, railway construction company. This company had built up a national reputation constructing railways, tracks, embankments, bridges viaducts and tunnels as they threaded the developing rail network through the British landscape. The company were responsible for working on key sections of the internationally famous Settle to Carlisle railway.

Navvies

Whilst it was the brilliance of engineers like Johnson and Abbott that designed the viaduct, it was the railway navvies who took on the hard graft of building the structure. Equipped with only the most basic of equipment, the navvies achieved amazing feats of engineering. The work was dangerous and over 500 navvies were killed annually in the construction of Britain’s railway network.

Image from The Wild Geese website

A local newspaper reported an accident during Bennerley’s construction.

“The poor fellow was adjusting a loose plank when he lost his balance and fell from a height of 40 feet head first upon the permanent way of the Midland Railway beneath. He was said to have been alive when taken up, but as we listened to the description of the eye-witnesses and glanced, with a shudder, from the dizzy height to the pool of blood, which told its own dread tale too well, we felt that the chances of recovery from such a shock must be indeed small.”

Bennerley Viaduct is a tribute to the graft and bravery of the railway navvy.

Fabricators

The viaduct is “locally sourced” with all of its wrought and cast iron component parts being fabricated in Derby. Some of the bricks which form the pier bases also have a Derby stamp on them. The large cast iron base plates and the wrought iron piers and trusses were all fabricated by Eastwood and Swingler, a Derby based iron work company who produced ironwork for railways on a global scale.

In some ways. Bennerley Viaduct is like a giant Meccano set. All the parts for the viaduct were pre-fabricated in Derby, transported to the site then assembled in situ at Bennerley using over half a million rivets.

Image: Garry Black

A Bespoke Design

The crossing of the Erewash Valley between Awsworth and Ilkeston provided a challenge to the engineers as the area was honeycombed with old mine-workings. The engineers concluded the ground could not support a traditional brick viaduct so to reduce loading on the foundations, the engineers designed a structure which was both light and flexible.

Pier bases: From the base up, the viaduct sits on brick pier bases. As the viaduct is on a 1:100 gradient, all of the pier bases are at different heights. The Awsworth end of the viaduct is 15 feet higher than the Ilkeston end.

Base Plates: The structure “floats.” Resting on top of each brick pier bases are 4 large cast iron base plates. These plates are not tied into the bases in any shape or form. They simply rest on the pier bases, held in place by gravity alone.

Columns: Attached to the cast base plates are 12 wrought iron columns which support the deck. The hollow columns are constructed from wrought iron quarter sections which have been riveted together. These are kept in position by horizontal and diagonal bracings which are tensioned using cotterpins. Over half a million rivets were used in the construction of the viaduct.

Deck: The deck of the viaduct consists of 526 transverse iron troughs which were filled with ballast. The sleepers which carried the railway lines were laid in the troughs. The track and most of the ballast has been removed.

Spans: The viaduct has 19 spans in total. Three spans cross over the Midland Railway. These spans are supported by brick piers. There are 16 further spans crossing the valley supported by 15 wrought iron piers.

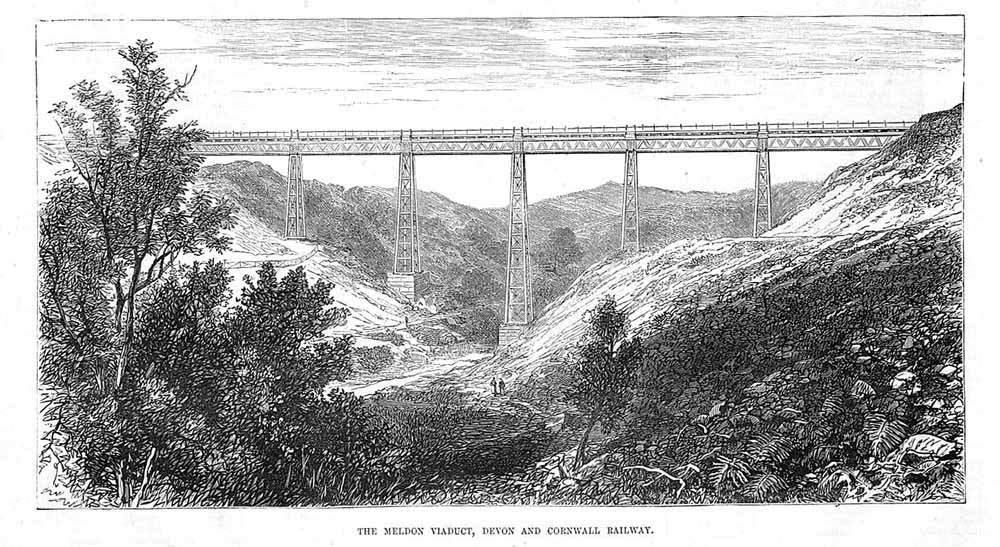

Condition: This wrought iron lattice work viaduct is 1452 feet long with the rails 60 feet 10 inches above the Erewash River. It is the longest wrought iron viaduct in the British Isles. The Meldon Viaduct in Devon is the only other wrought iron viaduct left standing in the UK. Bennerley Viaduct is a grade 2* listed structure giving it national importance. For its age, it is in remarkable condition and is largely unaltered since its construction.

Lifespan: 1878 – 1968

How long was the viaduct in use?

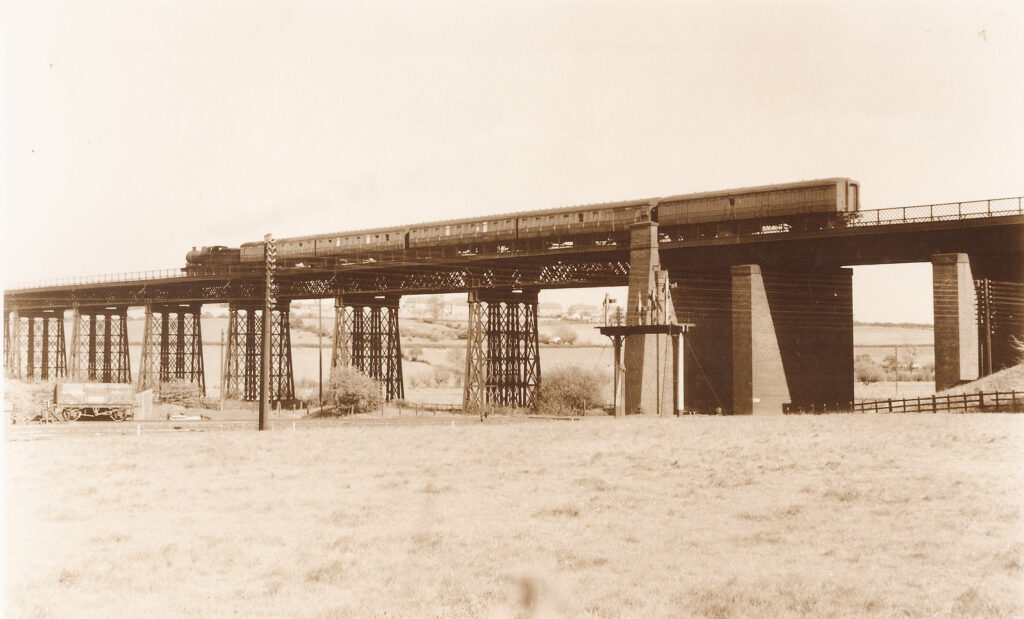

The Viaduct opened in January 1878 following an eighteen month construction period and went on to carry both goods and passenger traffic for the next 90 years. The revenues generated during this period repaid the heavy investment of the Great Northern Railway Company before its closure in 1968.

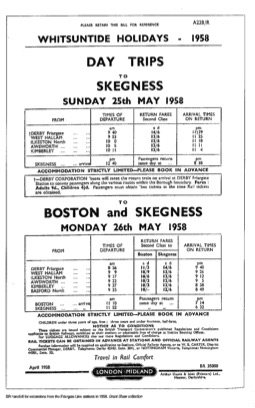

Goods trains carrying coal, iron ore or beer frequently rattled over the viaduct. Passenger trains gave local people access to both Nottingham and Derby. The line also brought the coastal resort of Skegness within reach and, on bank holidays, thousands of local people used to take a day trip to “Skeggy” at a bargain price of 13 /6d return – 67p in 1958 prices!

The Bennerley Viaduct carried freight and passengers for over 90 years with very little incident. The Beeching Report in 1963 recommended the line be closed for economic reasons and in 1964 the last passenger train went over the viaduct. The last goods train crossed the structure in 1968. The tracks were lifted in 1969 and the viaduct was closed. The structure no longer had a purpose and it became a liability for its owners, British Rail.

The tracks were then lifted and the structure became redundant.

Zeppelin Attack

Probably the most eventful moment in the history of the viaduct was the first world war Zeppelin bombing.

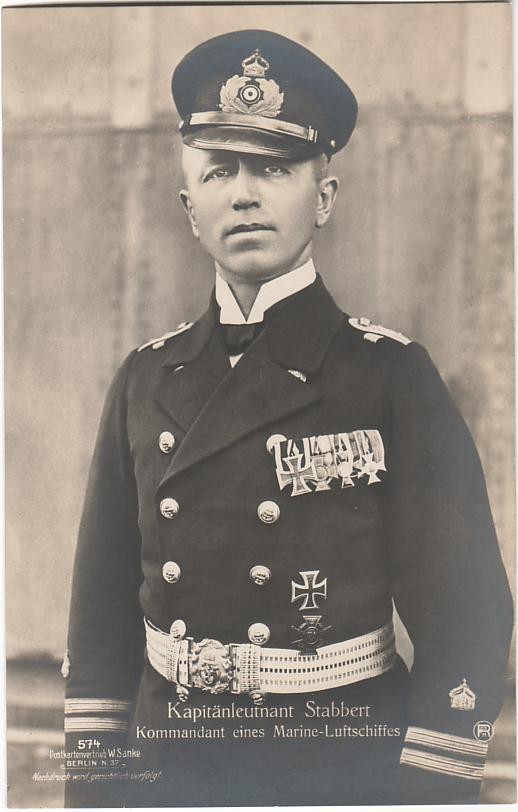

On Monday 31 January 1916, Kapitanleutnant Franz Stabbert and 17 crew travelled across the North Sea in Zeppelin L-20, along with a fleet of eight other airships, with Liverpool, Sheffield and Manchester as their targets. Due to bad weather, basic navigation and mechanical problems some of the airships became lost or had to turn back. Extensive thick fog combined with poor navigational equipment meant that the Zeppelins had very little idea where they were.

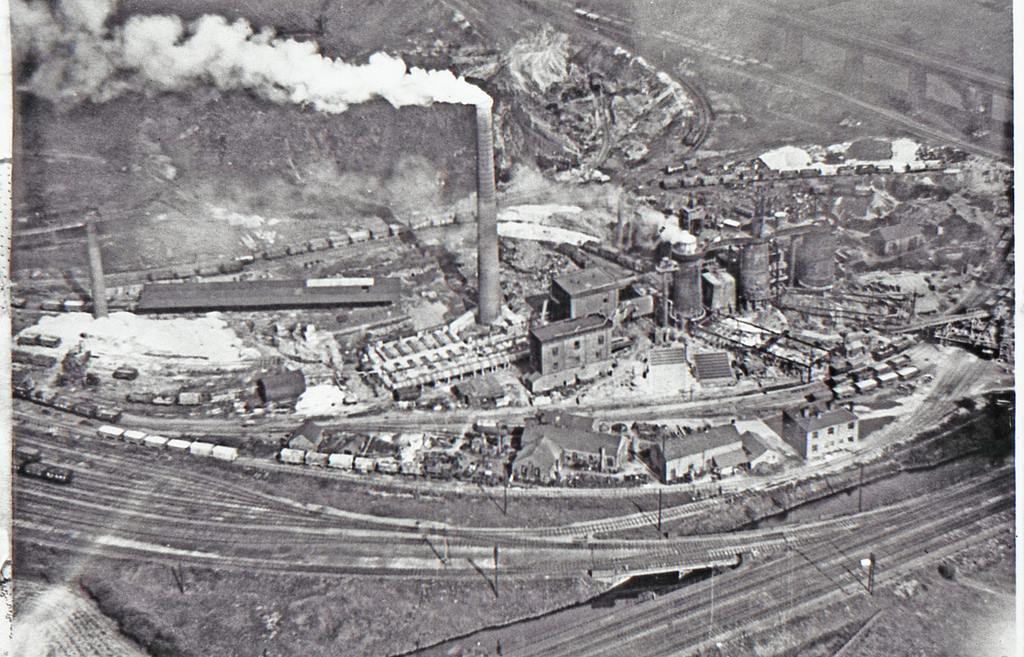

The Glow of Bennerley Ironworks

Kapitanleutnant Franz Stabbert, it is thought, was attracted to the glow coming from Bennerley ironworks and at 8.20 pm the L-20 loomed over Ilkeston. Here he dropped seven high explosive bombs, one of which fell just to the south of the viaduct on the Midland Railway line at Bennerley Junction. Shrapnel marks can still be seen on the viaduct. The Railway line was damaged along with a signal box and a cattle shed. As a result of the raids in the Ilkeston area, two men and a cow were killed.

Eye Witness Account from Awsworth

The stories of the bombing raid have passed down through generations. On that eventful night, Jessie Harrison lived with her parents, Eliza and William Harrison at No 5 Barlows Cottage, Awsworth. As a three year old girl, Jessie was awakened by a strange noise. She went to the window and saw a colossal, cigar like white shape fly through the night sky. Whilst looking through the window, Jessie accidentally set fire to the curtains with a candle. The story of seeing the Zeppelin and getting into trouble for igniting the curtains had a huge impact on someone so young. She retold the story throughout her life and the tale was passed down through her family.

Iron Cross made from Shrapnel

Jessie’s father, William Harrison retrieved some of the shrapnel from the bomb which fell to the south of the viaduct. William Harrison worked in one of the local pits and he gave the shrapnel to the blacksmith at the mine who fashioned the metal into a German Iron Cross. This cross was engraved with the words Air Raid, Bennerley, 31/1/16 and the “souvenir” was kept on the chain to his pocket fob watch.

Zeppelin L20 ditches in Norway

Airship crews were regarded as elite troops in Germany. . It certainly took guts to do what the crews of the zeppelins did – to get into a highly flammable ‘balloon’ and fly it across the North Sea knowing that if you were hit you would have very little chance of survival. On the L20’s second bombing mission, high winds carried the L20 miles off course and the craft ended up ditching into Hafrsfjord near Stavanger in Norway. Stabbert was captured and taken prisoner.

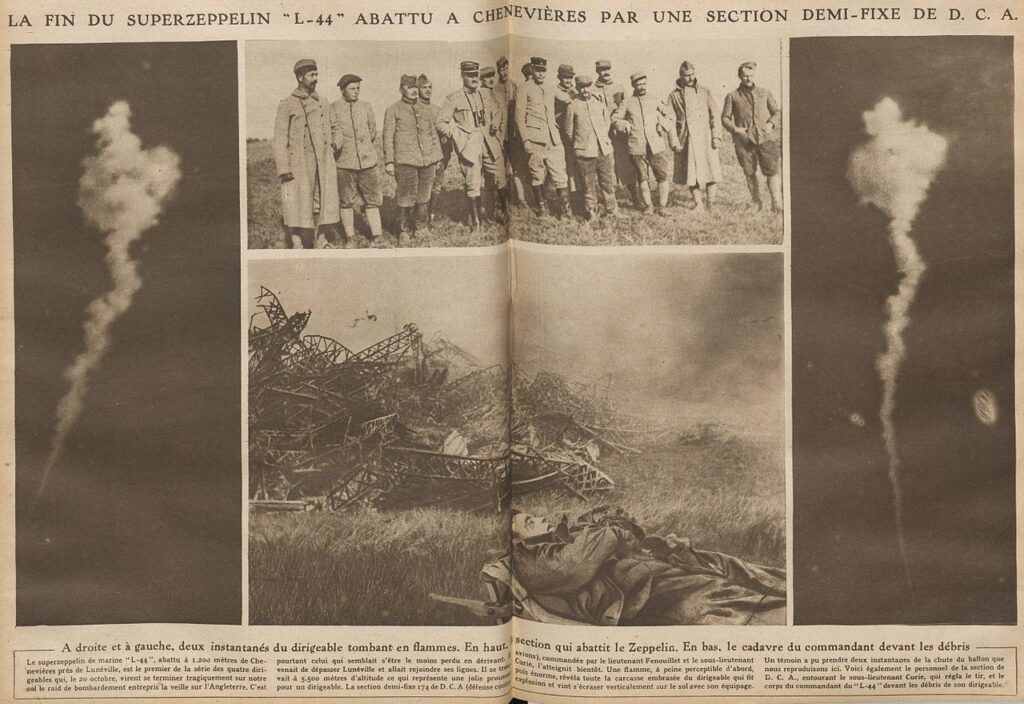

Zeppelin LZ 93 Shot Down

Stabbert escaped after six months of internment and he returned to flying Zeppelins. On 19th October 1917, the French army artillery shot down Stabbert’s Zeppelin LZ93 which was en route to England for another bombing raid. Stabbert and his crew were all killed in the attack and he was photographed in front of the wreckage.

A French Connection?

The “Eiffel” Viaduct

Over the years, newspapers have referred to Bennerley as “the Eiffel Viaduct” leading many to believe that Gustav Eiffel had some part in its construction. Eiffel did design some spectacular wrought iron viaducts such as the Garabit in the Massif Central and the Maria Pia bridge in Portugal. He is also internationally famed for constructions such as the Eiffel Tower and the internal support structure for the Statue of Liberty. Eiffel’s chosen material for most of his structures was wrought iron and he frequently used the kind of wrought iron latticework we can see in the Bennerley Viaduct. Other than those comparisons, Eiffel had nothing at all to do with Bennerley Viaduct.

The Busseau Viaduct

However, there may be a French connection. Bennerley was reputedly modelled on the Busseau Viaduct, designed by Wilhelm Nordling, which crosses the Creuse Valley in Central France. It is easy to see the similarities in construction between the Busseau and Bennerley as the wrought iron lattice design is integral to both structures. The Busseau is still in use today for railway traffic.

Image by Alan Albuary

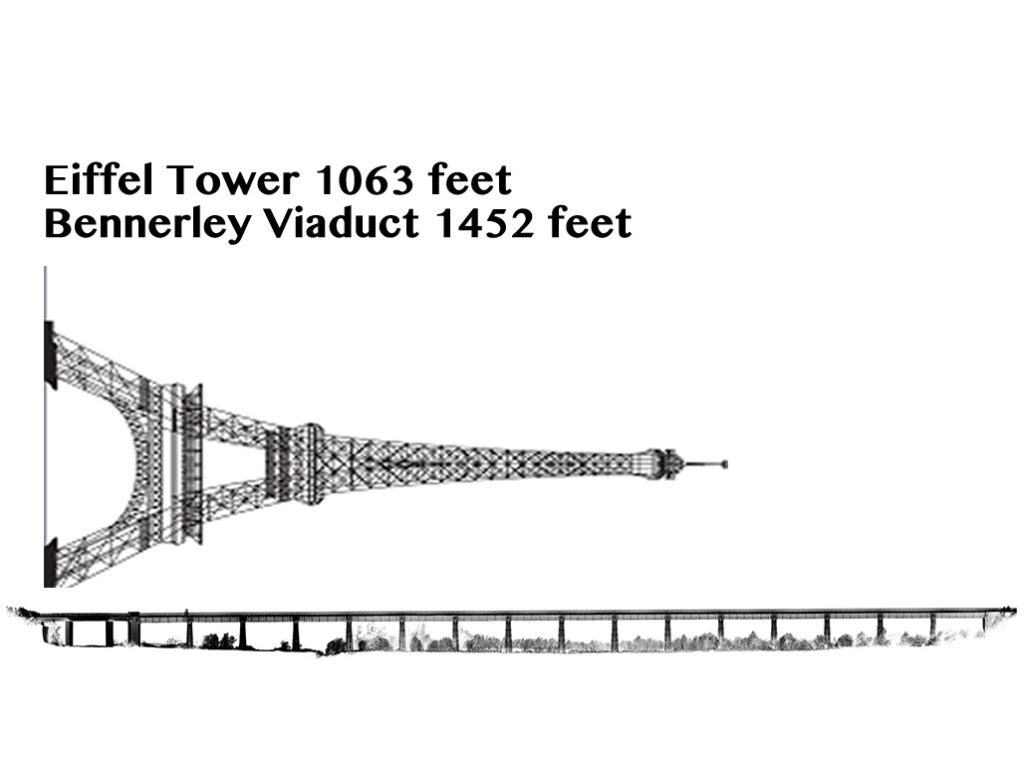

Two Iron Giants

Despite there being no direct connection with Eiffel, the viaduct still gets affectionately referred to as “Cotmanhay’s Eiffel Tower”. However, unlike the Eiffel Tower, Bennerley Viaduct was built as a commercial structure designed to perform a practical function whereas the Eiffel Tower was built as a temporary “showpiece” structure to demonstrate France’s prowess at the 1889 Paris Exposition. At that time, the Eiffel Tower was the tallest structure in the world by a considerable margin so it was clear that size mattered. On that note, if you put the Eiffel Tower on its side, Bennerley Viaduct would be nearly 400 feet longer! Bennerley Viaduct truly is an Iron Giant.

The Survivor

Bennerley Viaduct is a survivor making it through storms, floods and attempts to demolish. Other wrought iron viaducts such as the Crumlin, Dowery Dell, Staithes and Belah have all disappeared from the landscape. In the British Isles, only the Meldon (Devon) and Bennerley survive and on a global scale, there are few wrought iron viaduct that remain.

British Rail Seek Demolition

After the closure of the Friargate line in 1968, British Rail wanted to demolish the structure. The viaduct no longer had a purpose and its ongoing maintenance had become a financial liability for them. Tenders were sought for its demolition. Due to its wrought iron construction, it could not be cut up using conventional metal cutting equipment and wrought iron had little scrap value. The eye wateringly high cost of demolition gave the viaduct some respite.

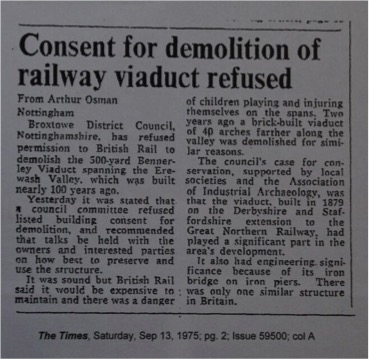

Application Refused

The viaduct was given grade 2* listing in 1974, a designation that gave the viaduct increased protection as it was deemed to be a structure of national importance. Undeterred, British Rail applied to Broxtowe Borough Council and Erewash Borough Council in 1975 to demolish but they were refused permission.

Public Enquiry

In 1980, the proposal to demolish went to public enquiry. Local people, councils and special interest groups joined forces to convince the government inspector that the viaduct was an invaluable feature of the country’s industrial and railway heritage. A proposal to repurpose the viaduct as a walking and cycling trail was put forward by the community.

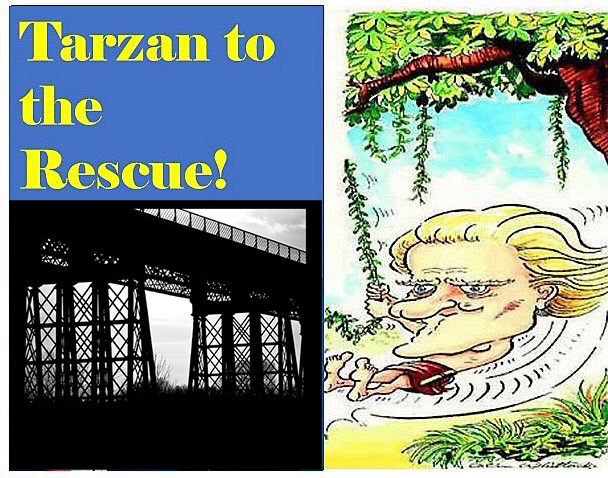

Tarzan to the Rescue

Environment Secretary Michael Heseltine gave the iron giant a temporary stay of execution requesting a feasibility study into the proposals to repurpose Bennerley Viaduct as a walking and cycling trail. The Bennerley Viaduct Preservation Trust was formed shortly afterwards. For nearly two decades, this group promoted the vision of re-opening the viaduct successfully countering those who sought the viaduct’s demolition.

Marooned and Abandoned

The abandonment of the viaduct had led to renewed calls for its removal by those who saw the viaduct as an eyesore and a safety risk. In the 1980s, the viaduct effectively sat in an opencast coal mine. The embankment on the eastern abutment was removed leaving the viaduct marooned and abandoned. Despite the calls of many seeking demolition, the viaduct survived.

resulting in British Coal losing their machinery.

Change of Ownership

In 1998, following the privatisation of the railways, the ownership of the viaduct was passed to Railway Paths Ltd, a sister charity to Sustrans. Over 200 miles of old trackbed and over 700 railway structures were given to RPL with the expectation that these routeways be incorporated into the emerging National Cycling Network.

Rediscovering Bennerley Viaduct

In 2015, Sustrans secured a £40,000 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund for a project called “Rediscovering Bennerley Viaduct.” The project sought to engage the community and assess the levels of support for bringing the viaduct back into use as a walking and cycling trail. The support from the community was strong and the Friends of Bennerley Viaduct (FoBV) was formed. In 2017 Sustrans, in partnership with the FoBV, developed an £8.3 million project to restore and repurpose the viaduct as a walking and cycling trail. Funding for the project was sought from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF).

Sustrans withdraw from Project

Heritage Lottery assessed the project and considered it to be a strong one. On its first attempt, the bid narrowly missed out on securing funding. HLF considered the project to be a priority recommending resubmission. Sustrans initially planned to submit a revised application but feared that match funding may not be available. In February 2018, Sustrans decided not to pursue the project passing responsibility for future projects back to the owners, Railway Paths Ltd.

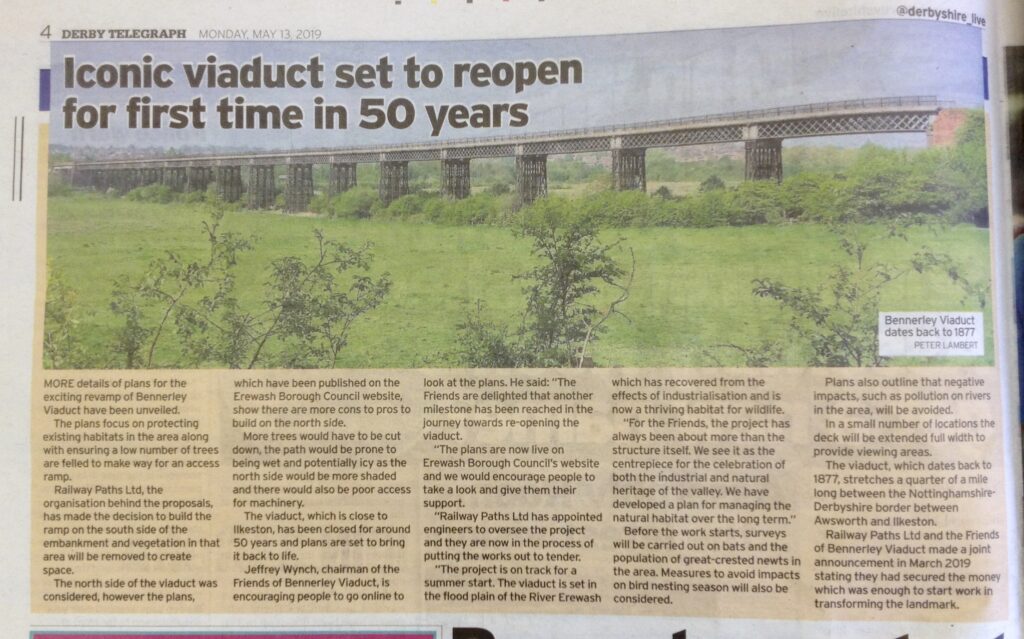

Access to Heritage

Since March 2018, the Friends of Bennerley Viaduct have worked closely with Railway Paths to develop an incremental project which aims to secure the future of the viaduct for generations to come. The first stage of the project “Access to Heritage” should lead to the viaduct being re-opened to the public in 2020 after 50 years of closure and abandonment.

Bennerley Viaduct – the Survivor

The viaduct escaped demolition by a combination of good fortune and by the efforts of so many people, councils and organisations who all continue to join forces to ensure it can be enjoyed by future generations. Bennerley Viaduct is a survivor.

Cultural Significance

The viaduct is a source of local pride uniting many sections of the community. It is an iconic symbol of the area’s rich industrial heritage and culture. Coal mining and ironworks once played a major role in the local economy. Bennerley Viaduct was used to transport coal and iron ore. Many older local people fondly recall crossing the viaduct on day trips to the seaside.

Many local groups have a specific interest in the viaduct including: railway enthusiasts; engineers; historical and archaeological societies; transport groups and many more. The viaduct provides inspiration for artists. The area beneath the viaduct is rich in wildlife and the community values its diverse natural heritage. The large numbers attending talks and guided walks bear witness to the huge community interest in the project and its cultural significance to them.

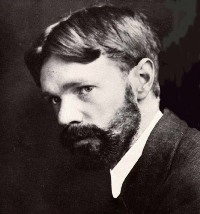

The writings of D. H. Lawrence have important local, national and international significance. Lawrence was born in Eastwood and the countryside of the Erewash Valley is the setting for many of his novels. He frequently refers to the viaduct in his writings.

The Friends Group has a growing membership. The members take part in regular work parties to increase the biodiversity of the immediate landscape and to make it accessible. The development of a walking and cycling trail will make a significant contribution to the creation of a sustainable transport infrastructure, important on a national and international level.

D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence was the son of a former school teacher and a Nottinghamshire coal miner, brought up in the small mining community of Eastwood at a time when modern industry began transforming the East Midlands countryside. He was one of the twentieth century’s most influential writers and arguably the most famous writer coming from working class origins.

D. H. Lawrence fondly referred to the Erewash Valley as the country of his heart. He walked through the countryside extensively and often contrasted the beauty of the landscape with the ugliness of the mines which he described as “accidents in the landscape”. He also wrote about the dehumanising effects of industrialisation. Even when he had left the Erewash Valley, he vividly remembered the beauty of the local countryside and the ugliness of industrialisation.

“To me it seemed and still seems an extremely beautiful countryside, just between the red sandstone and oak trees of Nottingham and the cold limestone, the ash trees, the stone fences of Derbyshire.”

Nottingham and the Mining Country 1919

D. H. Lawrence knew the area by the viaduct very well and refers to the viaduct directly in his writings. Lawrence’s fiancée lived in nearby Cossall Village so he would have walked past the viaduct regularly. He refers to the evocative sound of the rattle of trains going over the viaduct in Sons and Lovers. The rattle of the viaduct was a familiar sound to anyone who lived within earshot.

Image by T. G. Hepburn

‘There was a faint rattling noise. Away to the right, the train, like a luminous caterpillar, was threading across the night. The rattling ceased. “She’s over the viaduct. You’ll just do it.”’

D. H. Lawrence, Sons and Lovers, 1913

The setting of one of his most famous novels, “The Rainbow” is based in this part of the Erewash Valley. The view from the top of the viaduct affords excellent views of the countryside which inspired Lawrence.

“The Brangwens had lived for generations on the Marsh Farm, in the meadows where the Erewash twisted sluggishly through the alder trees separating Derbyshire from Nottinghamshire.”

D. H. Lawrence, The Rainbow, 1915

Image by Paul Atherley